Contemporary Fine Arts freut sich, in Kooperation mit Max Werner die Ausstellung Sons des New Yorker Künstlers Archie Rand (*1949, Brooklyn, NY) zu präsentieren.

It All Becomes a Song

Ein Text von Barry Schwabsky

Archie Rand malt heute keine einzelnen Bilder mehr – jedenfalls so gut wie nie – sondern widmet sich in sich geschlossenen Gemäldegruppen. Diese Gruppen jedoch sind keine erzählerischen Folgen, wie wir sie aus der klassischen europäischen Kunst kennen – etwa aus Giottos Darstellungen des Lebens Christi in der Cappella degli Scrovegni in Padua. Ebenso wenig handelt es sich um Serien, in denen ein einziges Motiv beharrlich variiert wird, wie in Claude Monets Heuhaufen. Und auch kein Themenzyklus, der ein bestimmtes Sujet aus unterschiedlichen Blickwinkeln beleuchtet, wie etwa Gerhard Richters 18. Oktober 1977.

Rands Werkgruppen beziehen sich oft auf einen Text – entweder auf die Arbeit eines modernen oder zeitgenössischen Dichters oder auf die jüdische Schrift- und Kommentarliteratur. Das bisher wohl bedeutendste Beispiel ist The 613 aus dem Jahr 2006: 613 Leinwände, entsprechend den 613 Mitzwot oder Geboten der hebräischen Bibel. Doch diese Texte werden nicht bloß illustriert. Das Wechselspiel zwischen Wort und Bild ist unberechenbar – es ist wild, manchmal grotesk und erinnert oft an frühe Comics oder expressive Taschenbuchcover – sogar in noch grelleren Farben. Allerdings beruht es auf Rands jahrzehntelanger Beschäftigung mit Talmudischer Gelehrsamkeit, die ihm erlaubt, assoziative Sprünge zu vollziehen, die den Meisten von uns verborgen bleiben. Rand sagte mir einmal: „Bild und Text müssen so fein austariert sein, dass man unablässig zwischen ihnen hin- und herspringt – bis alles zu einem Lied wird.“ (1)

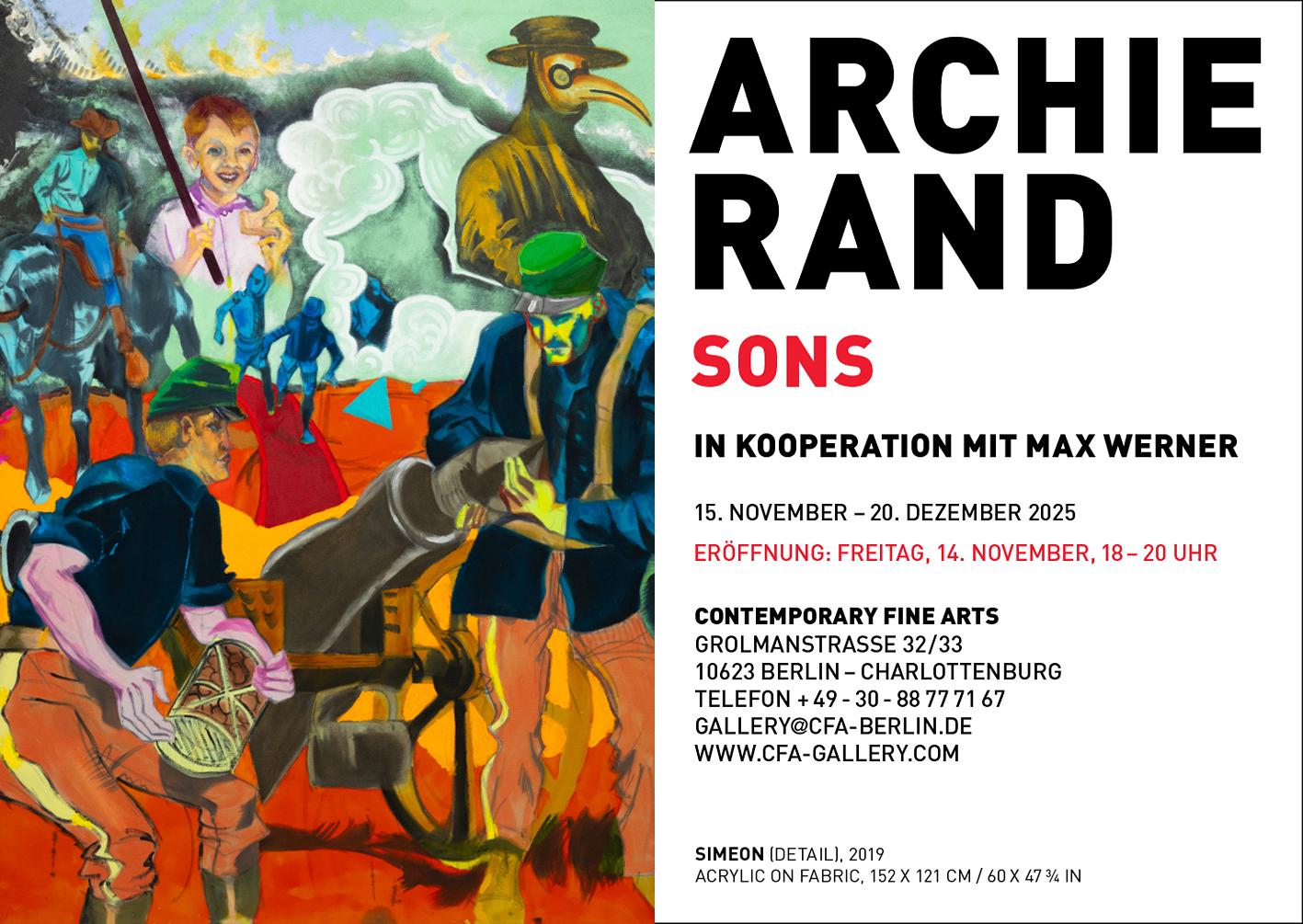

Rands Serie der zwölf Söhne hat einen anderen Ursprung – keinen textlichen, sondern einen kunsthistorischen. 2018 zeigte die Frick Collection in New York eine Folge von Gemälden aus der Mitte des 17. Jahrhunderts von Francisco de Zurbarán: Jakob und seine zwölf Söhne. Diese lebensgroßen, porträthaften Darstellungen lösen ihre Figuren aus der biblischen Erzählung, zeigen sie jedoch jeweils mit Attributen, die auf ihr Leben und Schicksal als Stammväter Israels verweisen. Ursprünglich wohl für Südamerika bestimmt, tauchten die Bilder im 18. Jahrhundert in England auf, wo ihr erster bekannter Besitzer ein portugiesisch-jüdischer Kaufmann war.

Angeregt durch Zurbarán beschloss Rand, seinen eigenen Zyklus über die zwölf Söhne zu malen – ohne Jakob, den Vater. Doch wie schon in anderen Serien wollte er sich nicht streng an die Vorlage halten und zeigte sich auch hier als ‚unfolgsamer Sohn‘ des Meisters aus Sevilla. (2) Anstatt – wie Zurbarán – die Söhne selbst zu malen, entschied er sich, ihre Träume darzustellen. Zwar haben die meisten der zwölf Bilder einen männlichen Protagonisten – aber ist dieser langhaarige Urmensch, der mit einem Dinosaurier ringt, wirklich Benjamin, der jüngste Bruder? Und sollen wir Zebulon mit jenem mittelalterlichen Krieger identifizieren, der in entgegengesetzte Richtung rennt, während eine Burgmauer erstürmt wird? Sicher nicht. Und dann gibt es Gemälde, in denen gar keine offensichtliche Verkörperung eines Sohnes vorkommt – am deutlichsten bei Issachar, dessen Bild zwei Cowgirls zeigt, die auf Pferden in entgegengesetzte Richtungen reiten.

Es braucht keine große Vorstellungskraft, um zu erkennen, dass diese zwölf Söhne zugleich Aspekte eines einzigen Sohnes sind: jenes von Ruth und Sidney Rand 1949 in Brooklyn, New York, geborenen Kindes. Diese von Soldaten, Rittern und Cowboys bevölkerten Gemälde – und mitunter auch von zechenden Großstädtern, die einem Mad Magazine-Cartoon entstiegen sein könnten – öffnen den Blick in die phantasiehafte Bilderwelt eines Kindes der amerikanischen Nachkriegskultur. Ein Kind, das aufwuchs mit den Little Golden Books, vor allem jenen, die Tibor Gergely illustrierte, und mit den EC-Comics (Tales from the Crypt, Weird Fantasy, Two-Fisted Tales). Hefte, die der junge Künstler heimlich las, denn im Hause Rand waren Comics verboten. Und das zu einer Zeit, in der Druckerzeugnisse noch das wichtigste Medium zur Verbreitung von Bildern waren – Bilder, deren Originale größtenteils von Hand gezeichnet oder gemalt wurden. Die Gemälde, die Rand aus diesen tief verinnerlichten Quellen heraufbeschwört, sind zutiefst autobiografisch – ohne jedes Selbstporträt, ohne Tagebuchton. Sie greifen einfach nach dem, was Jahrzehnte später im übervollen Gedächtnis eines visuell unersättlichen Kindes noch nachhallt. Rand betont, dass seine Arbeit frei von Nostalgie und auch frei von Ironie sei. Was die Nostalgie betrifft, gestehe ich ihm das gerne zu. Er lädt uns nicht dazu ein, mit ihm über die hübschen und komischen Dinge seiner Kindheit zu schmunzeln. Er blickt nicht herablassend auf sein früheres Ich. In diesen Bildern steckt, was er noch immer empfindet: Schrecken, Begehren, Sehnsucht, Verzweiflung. Sie beschwören eine Welt voller dunkler Ängste. Es gibt einen Grund, warum Rand Jakob – den Vater all dieser Söhne, die wiederum Stammväter ganzer Völker wurden – aus seinem Zyklus ausgeschlossen hat: Diese Söhne erscheinen schutzlos, verletzlich. Der väterliche Schutz wurde ihnen entzogen, wie bei einem Kind, das vom Vater ins Wasser geworfen wird, damit es lernt, zu schwimmen: „Wenn wir den väterlichen Arm verlassen haben und wie ein Stein aus der Schleuder ins Unbekannte geworfen werden, kann der erste Eindruck nur bittere Feindseligkeit sein.“ (3) Dieses Zitat stammt von Gaston Bachelard, der meinte, die tiefsten Bilder des Unbewussten entstammten der Natur – Bilder von Wasser, Feuer und so weiter. Doch das Meer, in das ein modernes Kind geworfen wird, ist der Ozean der Bilder.

Was die Ironie betrifft, vermute ich allerdings, dass Rand und ich sie unterschiedlich verstehen – und warum auch nicht? Es gibt viele Arten von Ironie. Was Rand ablehnt, ist jene Ironie, die – wie die Nostalgie – der persönlichen Distanzierung dient. Einverstanden. Doch Ironie kann auch mehr sein. Für mich ist Rands Kunst das, was Friedrich von Schlegel über jene „alten und modernen Gedichte“ schrieb, die „vom göttlichen Hauch der Ironie durchweht und von einer wahrhaft transzendentalen Possenhaftigkeit beseelt“ (4) seien. Diese transzendentale Possenhaftigkeit ist gewissermaßen das Wesen von Archie Rands Kunst. Ironie bedeutet hier die gelassene Gleichzeitigkeit mehrerer, scheinbar unvereinbarer Perspektiven, die gemeinsam ein Ganzes bilden. In Naftali spielt im Hintergrund jemand Blindekuh, während im Vordergrund ein Reiter sein Pferd antreibt, das sich umdrehen will – fort von fünf fernen Gestalten, die aussehen, als seien sie zufällig einem späten Degas-Aquarell entstiegen. Wie hängt all dies zusammen? Im Kopf eines Kindes, oder im Auge Gottes, ist es ein und dasselbe. Nur für uns anderen nicht. Und unser Bewusstsein darüber, dass wir dies – diesen Zusammenhang – nicht erkennen, ist es, was ich Ironie nenne. Wie Rands Freund John Ashbery es gesagt haben könnte: Es ist der Name jenes Liedes, das wir am besten kennen. (5)

Barry Schwabsky ist ein amerikanischer Kunstkritiker, -historiker und Dichter mit Sitz in New York. Er ist Kunstkritiker für The Nation und Mitherausgeber der internationalen Rezensionen von Artforum. Seine Texte sind unter anderem in Art in America, Flash Art und der London Review of Books erschienen. Er hat an Institutionen wie Yale, NYU und Goldsmiths unterrichtet und ist Autor von Words for Art und The Widening Circle sowie weiterer Bücher über moderne und zeitgenössische Kunst.

1 Archie Rand with Barry Schwabsky, The Brooklyn Rail (Februar 2016), https://brooklynrail.org/2016/02/art/archie-rand-with-barry-schwabsky/.

2 Ebd.

3 Gaston Bachelard, Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter, übersetzt von Edith R. Farrell (Dallas: The Pegasus Foundation, 1983), S. 166.

4 Friedrich Schlegel, Lucinde and the Fragments, übersetzt von Peter Firchow (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1971), S. 148.

5 John Ashbery, The Songs We Know Best, A Wave: Poems (New York: Viking Press, 1984), S. 3-5.

Contemporary Fine Arts is pleased to present, in cooperation with Max Werner, Sons, an exhibition by New York–based artist Archie Rand (*1949, Brooklyn, NY).

It All Becomes a Song

An essay by Barry Schwabsky

Archie Rand doesn’t paint single pictures anymore – almost never. He makes groups of paintings. They are not narrative sequences like those we are familiar with from classical European art, such as the life of Christ as depicted by Giotto in the Capella degli Scrovegni in Padua, nor are they series in which a single motif is relentlessly re-examined, as we find in modern painting – for instance, Claude Monet’s paintings of haystacks. And neither do they form a cycle approaching a given topic from diverse angles, in the manner of Gerhard Richter’s October 18, 1977.

Usually, Rand’s groups of paintings are bound to a textual reference – either the work of a modern or contemporary poet or, often, from the Jewish scriptural and exegetical tradition. Most noteworthy among these, so far, has been The 613, 2006. 613 canvases correspond to the 613 mitzvot or commandments given in the Hebrew bible. And yet the texts are not illustrated; the relation between them and Rand’s imagery – raucous, sometimes grotesque, often redolent of early comic books and pulp paperback covers, but with even more lurid colors – is capricious, albeit based on his decades-long immersion in Talmudic scholarhip, which allows him to make metaleptic associative leaps that may not be evident to most of us. As Rand once told me, “The image and text have to have a counterbalance so evenly weighted that you bounce back and forth and it all becomes a song.” (1)

Rand’s series of twelve Sons has a different origin – not textual but art-historical. In 2018 the Frick Collection in New York mounted an exhibition of a cycle of paintings made in the mid-seventeenth century by Francisco de Zurbarán, Jacob and His Twelve Sons – life-size portraitlike works that detach their subjects from their biblical narratives, though each figure carries objects emblematic of his life and fate as the progenitor of one of the Twelve Tribes of Israel. The paintings are thought to have been intended for a South American destination but somehow, in the eighteenth century, turned up in Britain, where their first known owner was a Portuguese Jewish merchant.

Inspired by Zurbarán, Rand determined to paint his own cycle about the twelve sons – omitting Jacob, their father. But just as he “did not want to be textually obedient” in his other series, he became a disobedient son to the Sevillian master. (2) Instead of depicting the twelve figures in themselves, as Zurbarán did, he would paint, not the sons, but the sons’ dreams. Yes, most of the twelve paintings have a male protagonist – but is that long-haired caveman in hand-to-hand combat with a dinosaur really Benjamin, the youngest of the twelve brothers? We can doubt it. Should we identify Zebulon with that medieval warrior running the other way while the castle wall is being scaled? No. And then there are the paintings with no obvious stand-in for a featured son, most obviously Issachar, whose painting features two cowgirls on horseback riding in opposite directions.

It takes no great leap of the imagination to understand that the twelve sons here are all aspects of one son, namely that of Ruth and Sidney Rand, born in Brooklyn in 1949. These paintings populated by GIs, knights, and cowboys (and the occasional tippling contemporary urbanites who might have come out of a Mad magazine satire) must be what serve as archetypal images in the mind of a child of postwar American urban culture, growing up on Little Golden Books (he was drawn in particular to those illustrated by Tibor Gergely) and EC Comics (Tales from the Crypt, Weird Fantasy, Two-Fisted Tales) – in secret, because comic books were forbidden in the Rand household. All this, remember, at a time when print was still the main medium for the dissemination of images – images whose originals were still mainly drawn or painted by hand. The paintings that Rand conjured from these deeply imbibed sources are profoundly autobiographical without any note of self-portraiture, without any evident diaristic content. They simply pluck from the air whatever still seems resonant, decades later, from the overstuffed memory of what must have been a singularly visually voracious child. For all that, Rand insists that this work is without nostalgia, and also without irony. Regarding nostalgia, I’ll concede the point. He’s not asking us to coo with him over the cute and funny things he loved as a kid. He doesn’t condescend to his young self. In these images are embedded the things he still feels: horror, desire, aspiration, despair. They conjure a world full of obscure anxieties. There is a reason Rand left Jacob – the father of all these sons who in turn became fathers of whole tribes – out of his cycle: These are vulnerable sons, left on their own without protection. Or the protection has been withdrawn, or (more to the point) is felt by the child to have been withdrawn, as when a father pitches his child into the water to sink or swim: “When we have left our father’s arms to be thrown ‘like a stone from a sling’ into the unknown element, there can be no other first impression than bitter hostility.” (3) Gaston Bachelard, whom I just quoted, imagined that the deepest images in the unconscious come from the natural world – images of water, of fire and so on. But the sea into which a modern child is thrown is the ocean of images.

As for irony, however, I suspect that Rand and I understand it differently. And why not? There are all kinds. What Rand rejects is the kind of irony that – just like nostalgia – enables personal disavowal. Agreed. But irony can be something more than that. For me, Rand’s art is like what Friedrich von Schlegel wrote of as those “ancient and modern poems that are pervaded by the divine breath of irony throughout and informed by a truly transcendental buffoonery.” (4) That last phrase, transcendental buffoonery, is one hundred percent Rand. Irony here means the serene copresence of multiple and apparently irreconcilable perspectives forming a totality. In Naftali, someone’s playing blind man’s bluff in the background while a horseman spurs on a steed that seems to want to turn back, away from the five distant riders who seem to have idly wandered in from a late Degas watercolor. What do these things have to do with each other? In a child’s mind, or the eye of God, they are all one – just not for the rest of us. Our knowing that we don’t know this is what I mean by irony. It’s the name of the song – as Rand’s friend John Ashbery might have said – we know best. (5)

Barry Schwabsky is an American art critic, historian, and poet based in New York. He is the art critic for The Nation and co-editor of international reviews at Artforum. His writings have appeared in publications such as Art in America, Flash Art, and the London Review of Books. He has taught at institutions including Yale, NYU, and Goldsmiths, and is the author of Words for Art and The Widening Circle, among other books on modern and contemporary art.

1 Archie Rand with Barry Schwabsky, The Brooklyn Rail (February 2016), https://brooklynrail.org/2016/02/art/archie-rand-with-barry-schwabsky/.

2 Ibid.

3 Gaston Bachelard, Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter, translated by Edith R. Farrell (Dallas: The Pegasus Foundation, 1983), p. 166.

4 Friedrich Schlegel, Lucinde and the Fragments, translated by Peter Firchow (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1971), p. 148.

5 John Ashbery, The Songs We Know Best, A Wave: Poems (New York: Viking Press, 1984), pp. 3-5.