CFA is pleased to open Travis Macdonald‘s first solo exhibition during Kunsttage Basel.

Idols in the Countryside

A shop window dressed with formal clothing glows on a street corner. Before it, a man stands on the sidewalk, and closer still to the painting’s surface is a car on which another man and woman lean. The couple, it seems, might be enjoying music, as might the standing man. It’s almost as if the scene were a comical skit transcribed from a television show: Characters spontaneously dance on street, backed by laughing track. But it’s also possible that the upright man, hands on head, hair swept back, is having an episode all his own, so very far away from his surroundings. As much as one might look, there is a part of the picture that, even as it comes close to easy emotional relief, remains unsettlingly distant, holding up the empty expanse between the extraordinary and the everyday, mystery and knowing, the aleatory and the analytic. And it appears that, behind the shop, in the painting’s more remote background, the color of that distance is red.

I see the diptych, Midland Formal (2025), by Travis MacDonald for the first time at the New Zealand-born, Berlin-based painter’s Tempelhof studio. It’s early morning. The nearest café is miles away. MacDonald makes coffee and invites me to join him for a cigarette at a large window that overlooks the neighboring sandblasters’, where two men are at work, blasting. We watch on unnoticed. After excusing the lack of comforts in the room, MacDonald begins to pull paintings out of hiding. “I’ve been thinking about idols,” he tells me. “Main characters and supporting characters – a cast of people, like in a long-running sitcom. I make episodes, take a still, and it just doesn’t end.”

But it does begin. And that episode, I learn, sitting at a makeshift desk opposite MacDonald, was set on the North Island of New Zealand, in the small inland town of Bunnythorpe, where the artist was born in 1990. His mother, Kathryn McCool, was a photographer, and his father, Craig MacDonald, worked at an abattoir and as a technician for New Zealand sculptor Paul Dibble. A meaningful event came early. When MacDonald was all but six, his father, on an upskilling assignment for Dibble, relocated the family to the even smaller Australian town of Elphinstone, population 200. “Growing up, there was a general atmosphere of homesickness,” the artist says. For one, he missed all the greenery.

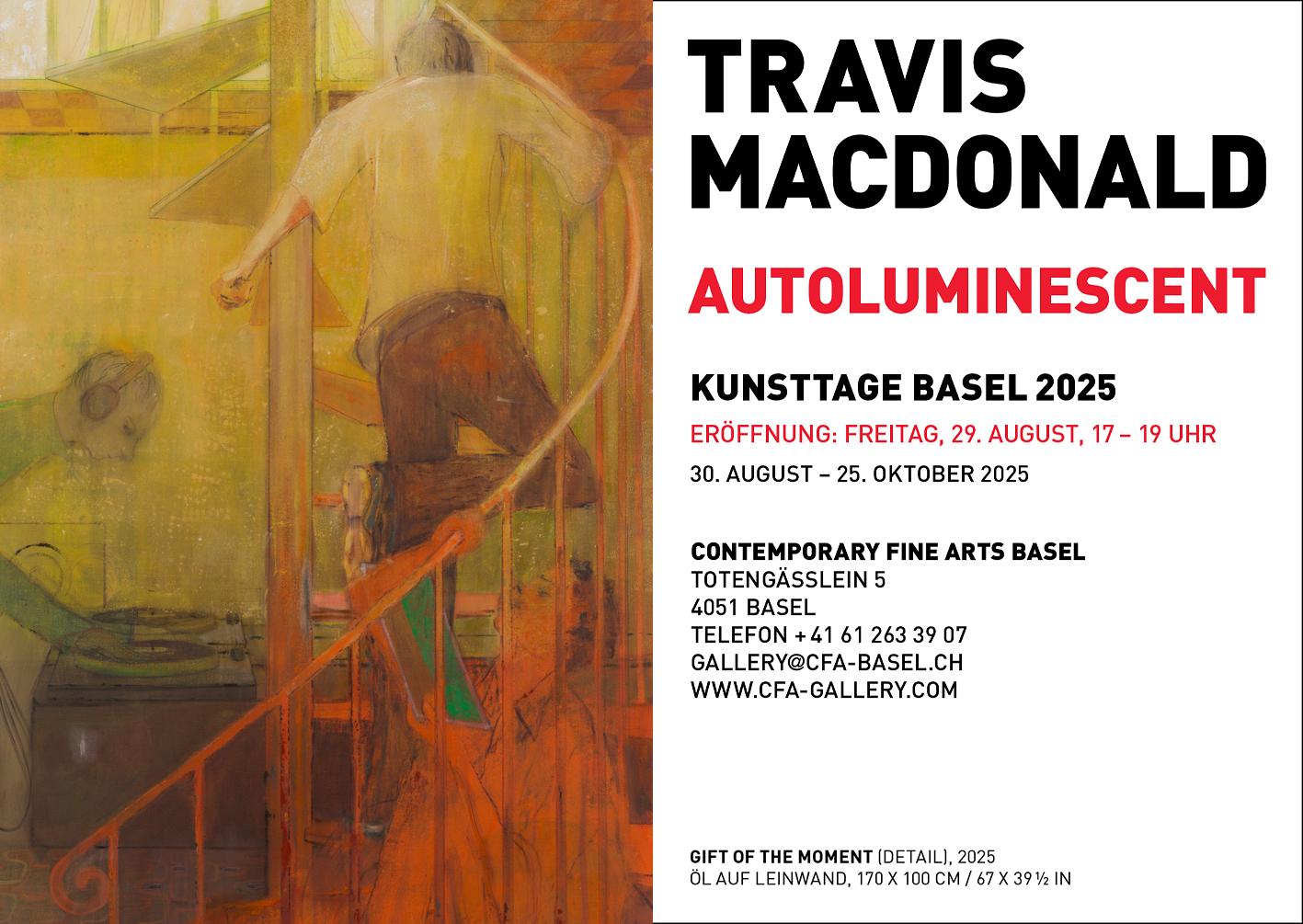

At a great distance from any major art institution, MacDonald nonetheless spent a good deal of time flipping through his parents’ few art magazines and books, bringing those discovered ideas into dialogues with his mother. “She would be working, driving around and looking for scenes to photograph, and I would sometimes tag along,” he says. “It was as if we were casting for a film. It’s how I learnt to look, not critically but analytically.” That analytic vision today plainly directs the composition of MacDonald’s paintings: in Midland Formal, for example, in the distances all so sharply defined, and in Gift of the Moment (2025), whose basic forms – rectangles, squares, circles – also fall into frame with the expressive geometry of the likes of Kazimir Malevich.

Music, too, was a way outside of Elphinstone for the teenage MacDonald. Drawn to punk and rock and roll, he began to regularly make the one-and-a-half-hour train ride to Melbourne, where he played in bands inspired by Flying Nun, the fabled New Zealand record label. Eventually he relocated to the cultural center, studying fine art at the city’s Victorian College of the Arts, and he continued with his music. This period was as serious as it was short lived. By 26, MacDonald had, “in a self-flagellating kind of way,” thrown in the Melbourne music scene. “I didn’t want to stop, but I needed to focus on painting,” he says, rising from the table and making his way across the studio to another stack of works. But while he left the scene, he didn’t depart the show, even as he later relocated to Europe. The Basel exhibition, for instance, is titled Autoluminescent, after a song by Australian post-punk legend Rowland S. Howard, and the artist will quietly confess that, from time to time, he still records music in private.

MacDonald, now with a painting in hand, holds it first in front of other works, then briefly in the sunlight streaming in from the windows. In this moment of silence, the thing seems to almost produce its own light, to glow from within. At my astonishment, the artist allows himself a quick smile. “Silk,” he says. While the use of the material in painting is certainly not new – it dates back to ancient Asian art, selected for reasons of economy – MacDonald brings out an overlooked quality: translucence. As light so magnificently pervades both pigment and textile, one wonders why, outside of Edgar Degas’s Fan paintings, the photophilic Impressionists did not make more use of the fabric as substrate.

Yet, it is more fitting, when we talk about MacDonald, to talk about the Nabis. The post-Impressionists of the late-nineteenth century had a fondness for the symbolic, for lifting meaning out of reality, and MacDonald’s recurring trees, wheels, and metal structures fall into this domain, despite the artist’s reluctance to speculate on their significance. As well, glimmers of Pierre Bonnard appear all around the studio, and especially, I soon find, in MacDonald’s use of the photograph. Like Bonnard, he views it as a material to mediate, to arrange. “The photos don’t translate immediately to a painting,” he says, pointing to the analytic aspect of his work. “I construct the images. They have to be rebuilt.” Some photographs he takes himself, using his phone, and others he selects from Instagram Stories, a medium he admits often sets alight his jealousy. “I’m screen-shotting all these stories of my friends doing the things I wish I was doing, having fun. But I’m not there. I’m here, wherever this is,” he says, shrugging at the studio, “inside a painting.” The works are in a way addressed to the jealousy that arises in the distance MacDonald has from his pals, who, in their broadly described expressions, in their aloofness, convey the anticipation and excitement found in a good night out – the aleatory sense that anything could happen.

That is one method or two. But sometimes, the artist tells me, writing can prefigure the photograph. In this channel, he describes in great detail, using the Notes application on his phone, what would make a good painting, what hasn’t been painted before, basing those observations on things either seen or imagined. Sentences in hand, he searches the Internet for images to, in his words, “reverse engineer” the painting, collaging together a constructed scene. And occasionally, with yet another nod to the Nabis and their democratic spirit, the found image is printed and pasted straight onto the painting itself. Through it all, the aspect of analytic assemblage is ever-present.

Two more paintings of the same motif, displayed by MacDonald one on top of the other, catch my attention – Crowdsurfer I and Crowdsurfer II. Rendered in shades of red and yellow, a lanky, long-haired man lies on his back, crowd surfing above a sea of hands, recalling the supine Jesus in Hans Holbein’s The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb. But while the “Dripping Man,” as the artist calls him, is put in the place of the Son of God, or of the idol – the distant figure to which, MacDonald reminds me, painting has always been in service – it’s clear that he does not possess the same immaculate qualities. “I’m aggrandizing and heroizing the underconfident, the depressive, the gravity-stricken,” the artist says, rolling another cigarette. I think of MacDonald and his mother in the car in the countryside, and back at the studio window, him and I both reminisce about growing up as long-haired louts on the other side of the world, where to have hair past the collar was to be considered gay or a hippy or both. “There’s the sociological part,” he says, “but the Dripping Man is also a way of breaking the geometry, formally speaking.”

Where one finds “the Drip,” one finds the meddling of materiality. The analytic is upset by the aleatory, and not only in the character’s outer appearance. Gravity, as MacDonald hinted, has also played a role in his becoming – “Paint should be wet,” he says as we watch the two working men get back to their sandblasting. In Jumbo Vision (2025), lingering just behind his friends and yet positioned center stage, the sappy man is painted in this way, resembling a drip and really dripped, intruding on the linear aspect of the buildings and bridge and the road beneath, speeding away to a vanishing point. Admittedly a bit embarrassed by his subtle drips, MacDonald, in using them among his rule-abiding geometries, gracefully brings chance into the picture. Anything could happen, and perhaps that could be something new, but perhaps not.

“In a way, doubt is the most important variable in painting,” MacDonald tells me, putting out his cigarette. It’s a burdensome emotion that either paralyses or drives, that outlines the expanse between what is known and what is not. “Doubt and devotion, they go hand in hand,” he continues. “And to devote myself to painting is a way to explain things to myself.” Where he differs from the Nabis, what makes him contemporary, is precisely his personal contextualization of the world and of the painterly tradition. He will not be writing any Définition du néo-traditionnisme, no manifesto. Travis MacDonald is devoted to painting for himself alone, and done his way, in the distance between the many articulations of the aleatory and analytic, one is taken into the painting to perhaps feel in themselves the kinds of things the artist feels – and to perceive his art and art history in a new light, at the same time both social and aesthetic.

Given the exhibition’s title and content, and knowing something of MacDonald’s life, it’s hard not to see the paintings in Autoluminescent as scenes from the artist’s earlier Melbourne days, stills from the series finale. The house parties and the hierarchies; the gossip and the drama. But it’s also MacDonald and his mother in the car again, chancing upon and giving form to the idols in the countryside. “The old notion of just depicting or observing,” he says, “this passiveness is relevant. And that’s all we’re left with now. The simple things.”

Text: Benjamin Barlow

CFA freut sich die erste Einzelausstellung Travis MacDonalds zu den Kunsttagen Basel zu eröffnen.

Idole auf dem Land

Ein leuchtendes Schaufenster mit schicker Kleidung an einer Straßenecke. Auf dem Bürgersteig davor steht ein Mann, links von ihm am Bildrand ein Auto, an das sich ein weiterer Mann und eine Frau lehnen. Das Paar und der Mann vorm Schaufenster hören offenbar Musik. Der Moment wirkt fast wie eine skurrile Szene aus einer Fernsehsendung: Charaktere tanzen spontan auf der Straße, untermalt von Gelächter aus dem Off. Es könnte aber auch sein, dass sich der stehende Mann seiner Umgebung kaum bewusst ist und ganz in sich selbst versunken mit den Händen durch sein nach hinten gekämmtes Haar fährt. Egal, wie genau wir auch hinschauen: Ein Teil des Bildes verspricht zwar emotionale Erleichterung, bleibt aber beunruhigend distanziert, ein leerer Raum zwischen Außergewöhnlichem und Alltäglichem, Geheimnisvollem und Erkennbarem, zwischen Zufälligen und Analytischen wird aufrechterhalten. Und es scheint, dass hinter dem Laden, im entfernten Hintergrund des Gemäldes, die Farbe dieser Distanz Rot ist.

Ich sehe Travis MacDonalds Diptychon Midland Formal (2025) zum ersten Mal im Tempelhofer Atelier des in Neuseeland geborenen und in Berlin lebenden Malers. Es ist früh am Morgen. Das nächste Café meilenweit entfernt. MacDonald kocht Kaffee und lädt mich ein, mit ihm am großen Fenster eine Zigarette zu rauchen. Unbemerkt beobachten wir zwei Männer, die in der benachbarten Sandstrahlwerkstatt arbeiten. Nachdem er sich für die spärliche Ausstattung des Raumes entschuldigt hat, beginnt MacDonald, Gemälde aus der Deckung hervorzuholen. „Ich habe über Idole nachgedacht“, erzählt er mir. „Haupt- und Nebenrollen – eine ganze Besetzung, wie in einer langjährigen Sitcom. Ich arbeite an Episoden, halte ein Still fest, und die Handlung hört einfach nie auf.“

Aber irgendwo beginnt sie. Und diese Episode, wie ich an einem provisorischen Schreibtisch, MacDonald gegenübersitzend erfahre, spielt sich auf der Nordinsel Neuseelands ab, in der kleinen Stadt Bunnythorpe im Landesinneren, wo der Künstler 1990 geboren wurde. Seine Mutter, Kathryn McCool, war Fotografin, und sein Vater, Craig MacDonald, arbeitete in einem Schlachthaus und als Techniker für den neuseeländischen Bildhauer Paul Dibble. Ein einschneidendes Ereignis ereignete sich, als MacDonald gerade einmal sechs Jahre alt war. Um eine Fortbildung für Dibble zu absolvieren, zog der Vater mit der Familie nach Australien, in die noch kleinere Stadt Elphinstone mit nur 200 Einwohnern. „Als ich aufwuchs, spürte ich eine allgemeine Atmosphäre von Heimweh“, sagt der Künstler. Zum Beispiel vermisste er das Neuseeländische Grün.

Obwohl er weit entfernt von allen großen Kunstinstitutionen lebte, verbrachte MacDonald viel Zeit damit, die wenigen Kunstzeitschriften und -bücher seiner Eltern durchzublättern und die darin entdeckten Ideen mit seiner Mutter zu diskutieren. „Sie arbeitete, fuhr herum und suchte nach Motiven zum Fotografieren, und ich begleitete sie immer wieder“, erzählt er. „Es war, als würden wir für einen Film casten. So habe ich gelernt, nicht kritisch, sondern analytisch zu betrachten.“ Diese analytische Sichtweise bestimmt heute ganz klar die Komposition von MacDonalds Gemälden: In Midland Formal beispielsweise, wo alle Entfernungen so scharf definiert sind, und in Gift of the Moment (2025), dessen Grundformen – Rechtecke, Quadrate, Kreise – mit der ausdrucksstarken Geometrie eines Kazimir Malevich in den Rahmen fallen.

Auch Musik war für den Teenager MacDonald ein Weg, Elphinstone zu entfliehen. Er fühlte sich zu Punk und Rock ‘n’ Roll hingezogen und fuhr regelmäßig mit dem Zug eineinhalb Stunden nach Melbourne, wo er in Bands spielte, die von Flying Nun, dem legendären neuseeländischen Plattenlabel, inspiriert waren. Schließlich zog er in das kulturelle Zentrum der Stadt, studierte Bildende Kunst am Victorian College of the Arts und machte weiter Musik. Diese Phase war ebenso ernsthaft wie kurzlebig. Mit 26 hatte MacDonald „auf eine selbstzerstörerische Art und Weise” die Musikszene von Melbourne hinter sich gelassen. „Ich wollte nicht aufhören, aber ich musste mich auf die Malerei konzentrieren”, sagt er, steht vom Tisch auf und geht quer durch sein Atelier zu einem weiteren Stapel von Werken. Er verließ zwar die Szene, nicht aber die Show, auch später nicht, als er nach Europa zog. So trägt die Ausstellung in Basel beispielsweise den Titel Autoluminescent, nach einem Song der australischen Post-Punk-Legende Rowland S. Howard, und der Künstler gesteht leise, dass er von Zeit zu Zeit immer noch privat Musik aufnimmt.

Inzwischen hat MacDonald ein Gemälde in der Hand, er hält es zunächst vor andere Werke und dann kurz in das Sonnenlicht, das durch die Fenster strahlt. In diesem Moment der Stille scheint das Bild fast sein eigenes Licht zu erzeugen, von innen zu leuchten. Über meine Verwunderung lächelt der Künstler kurz. „Seide“, sagt er. Die Verwendung dieses Materials in der Malerei ist zwar keineswegs neu – sie reicht bis in die alte asiatische Kunst zurück, wo es aus wirtschaftlichen Gründen ausgewählt wurde –, doch MacDonald bringt eine übersehene Eigenschaft zur Geltung: die Transluzenz. Da das Licht sowohl die Pigmente als auch den Stoff so wunderbar durchdringt, stellt sich mir die Frage, warum die lichtliebenden Impressionisten – abgesehen von Edgar Degas für seine Fächer-Gemälde – nicht häufiger Seide als Malgrund verwendet haben.

Wenn wir über MacDonald sprechen, so sollten wir uns aber mit der Künstlergruppe Nabis befassen. Die Postimpressionisten des späten 19. Jahrhunderts hatten eine Vorliebe für das Symbolische, für das Herauslösen von Bedeutung aus der Realität. MacDonalds wiederkehrende Bäume, Räder und Metallkonstruktionen fallen in diesen Bereich, auch wenn der Künstler sich weigert, über ihre Bedeutung zu spekulieren. Auch Pierre Bonnard ist überall im Atelier zu erkennen, insbesondere, wie ich schnell feststelle, in MacDonalds Umgang mit der Fotografie. Wie Bonnard betrachtet er sie als Material, das es zu vermitteln und zu arrangieren gilt. „Die Fotos lassen sich nicht sofort in ein Gemälde übertragen“, sagt er und verweist auf den analytischen Aspekt seiner Arbeit. „Ich konstruiere die Bilder. Sie müssen neu aufgebaut werden“. Einige Fotos macht er selbst mit seinem Handy, andere wählt er aus Instagram aus, einem Medium, das, wie er zugibt, oft seinen Neid entfacht. „Ich mache Screenshots von all diesen Stories meiner Freunde, die Spaß haben und Dinge unternehmen, die ich auch gern tun würde. Aber ich bin nicht dabei. Ich bin hier, wo auch immer das ist“, sagt er und zuckt mit den Schultern in Richtung Atelier, „in einem Gemälde“. MacDonalds Werke befassen sich in gewisser Weise mit diesem Neid, der aus der Distanz entsteht, den er empfindet, wenn seine Freunde in ihrer ausführlichen Expressivität und gleichzeitigen Unnahbarkeit die Vorfreude und Aufregung eines gelungenen Abends vermitteln – das aleatorische Gefühl, dass alles passieren könnte.

Das sind ein, zwei Methoden. Aber manchmal, so erzählt er mir, kann das Schreiben ein Foto vorwegnehmen. Dann beschreibt MacDonald mit Hilfe der Notizen-App seines Telefons sehr detailliert, was ein gutes Bild ausmacht und was noch nie zuvor gemalt wurde. Er stützt sich dabei auf tatsächlich Gesehenes oder Beobachtungen, die in seiner Vorstellung entstehen. Seine Beschreibung zur Hand, durchsucht er das Internet nach Bildern, um das Gemälde, wie er es nennt, „zurückzuentwickeln“ und eine konstruierte Szene zu collagieren. Gelegentlich – in einer weiteren Anspielung auf die Nabis und ihren demokratischen Geist – druckt er das gefundene Image aus und klebt es direkt auf das Gemälde. Der Aspekt der analytischen Assemblage ist dabei stets präsent.

Zwei Gemälde mit gleichem Motiv, die MacDonald übereinander aufgestellt hat, ziehen nun meine Aufmerksamkeit auf sich – Crowdsurfer I und Crowdsurfer II. In Rot- und Gelbtönen gehalten, liegt ein schlaksiger, langhaariger Mann auf dem Rücken und surft auf einem Meer von Händen. Es erinnert an den liegenden Jesus in Hans Holbeins Der Leichnam Christi im Grabe. Doch während der „Tropfende Mann“, wie der Künstler ihn nennt, an die Stelle des Sohnes Gottes oder des Idols gesetzt wird – jener distanzierten Figur, der die Malerei, wie MacDonald mich erinnert, immer gedient hat –, ist klar, dass er nicht über dieselben makellosen Eigenschaften verfügt. „Ich verherrliche und heroisiere die Unsicheren, die Depressiven, die von der Schwerkraft Gebeutelten“, sagt der Künstler und dreht sich eine weitere Zigarette. Ich stelle mir MacDonald mit seiner Mutter im Auto auf dem Land vor, und zurück am Atelierfenster erinnern wir uns beide, wie wir als langhaarige Rowdys auf der anderen Seite der Welt aufgewachsen sind, wo man bereits mit Haaren, die über den Kragen ragten, als schwul oder Hippie oder beides galt. „Das ist der soziologische Aspekt“, sagt er, „aber der Tropfende Mann ist auch eine Möglichkeit, die Geometrie zu durchbrechen – formal gesehen.“

Wo „der Tropfen“ zu finden ist, findet sich auch die Einmischung der Materialität. Das Analytische wird durch das Aleatorische gestört und das nicht nur in der äußeren Erscheinung der Figuren. Die Schwerkraft hat, so MacDonald, ebenfalls eine Rolle bei der Entstehung gespielt – „Farbe sollte nass sein“, sagt er, während wir den beiden Arbeitern wieder beim Sandstrahlen zusehen. In Jumbo Vision (2025) steht ein sentimentaler Mann direkt hinter seinen Freunden und dennoch im Mittelpunkt der Szene. Er ist auf diese Weise gemalt: Er ähnelt einem Tropfen und ist tatsächlich getropft. So dringt er in die Linearität der Gebäude, der Brücke und der Straße ein und rast auf einen Fluchtpunkt zu. Zwar machen MacDonald seine subtilen Tropfen etwas verlegen, doch indem er sie in seine regelmäßigen Geometrien einfließen lässt, bringt er auf elegante Weise den Zufall ins Bild: Alles könnte passieren, und vielleicht wäre das etwas Neues, vielleicht aber auch nicht.

„In gewisser Weise ist Zweifel die wichtigste Variable in der Malerei“, sagt MacDonald und drückt seine Zigarette aus. Es ist ein belastendes Gefühl, das entweder lähmt oder antreibt, das die Kluft zwischen Bekanntem und dem Unbekanntem aufzeigt. „Zweifel und Hingabe gehen Hand in Hand“, fährt er fort. „Und mich der Malerei zu widmen, ist eine Möglichkeit, mir selbst Dinge zu erklären.“ Was ihn von den Nabis unterscheidet, was ihn zeitgenössisch macht, ist genau seine persönliche Kontextualisierung der Welt und der malerischen Tradition. Er wird keine Définition du néo-traditionnisme schreiben, kein Manifest. Travis MacDonald widmet sich der Malerei allein für sich selbst, auf seine eigene Art und Weise. In der Distanz zwischen den vielen Ausdrucksformen des Aleatorischen und Analytischen werden wir beim Betrachten in das Gemälde hineingezogen, um vielleicht selbst das zu fühlen, was der Künstler fühlt – und um seine Kunst und die Kunstgeschichte in einem neuen Licht wahrzunehmen, auf soziale und ästhetische Weise.

Angesichts des Titels und der Inhalte der Ausstellung und dem Einblick in MacDonalds Leben fällt es schwer, die Gemälde in Autoluminescent nicht wie Szenen aus seiner Zeit in Melbourne zu betrachten – wie Stills aus dem Serienfinale: die Hauspartys und die Hierarchien, der Klatsch und das Drama. Aber dann auch wieder MacDonald und seine Mutter im Auto: Zufällig begegnen sie den Idolen auf dem Land und geben ihnen Gestalt. „Die alte Vorstellung, nur darzustellen oder zu beobachten“, sagt er, „diese Passivität ist relevant. Und das ist alles, was uns jetzt noch bleibt. Die einfachen Dinge.“

Text: Benjamin Barlow